Double life of Gitta

The most fascinating element of every genealogical search is that, at the beginning, there is absolutely no chance of predicting where the quest will end. Sometimes it is even hard to distinguish what the end itself is - or shall we say, there is no end, because our existence is the very continuation of the genealogical line itself. Yes, some day in the future some poor researcher may be wondering what our life path was about. Are we making his future work easier or harder? The results of the search are always astonishing, and even in cases of limited discoveries the process of searching is often more illuminating and gratifying for the people involved than are the hard facts and documents that might be discovered. The quest is the very essence of the process because, in order to untangle complicated family history, we have to follow many paths of local history, find and decipher documentation that is not always accurate, face different people and their elusive memories, and at the end amalgamate it all into one coherent picture.

It is a little bit like working with a jigsaw puzzle; not the brand-new set of 100 pieces, but a very old one with a couple of thousand pieces - an old one which has experienced a lot of wear and tear. Five generations of children played with the set, so many of the pieces have been lost. The ones that are left have been stained, creased and sometimes cut deliberately to fit the other deformed ones. They bear all the traces of usage, care, bewilderment, passion and destruction, all the traces of life and history around them. One piece seems to be from some other set, the other is blurred and faded due to time, the third one is missing and although we seem to have all other pieces around it, we will never get this element of the picture precisely. The worst thing is that the box that contained our set is gone, so we have no idea what the complete picture is supposed to look like. Thanks to some knowledge of history, plus rumor-based family stories, we have a vague idea of what the background picture of our puzzle is going to be. This factual but yet still intangible background becomes the fabric of our hectic puzzle. Where does one start such work??? You always start with the piece of the puzzle that seems the best preserved, the one that can support the complete picture. Sometimes, that's the only piece you have...

Gitta seemed to be a piece puzzle like that.

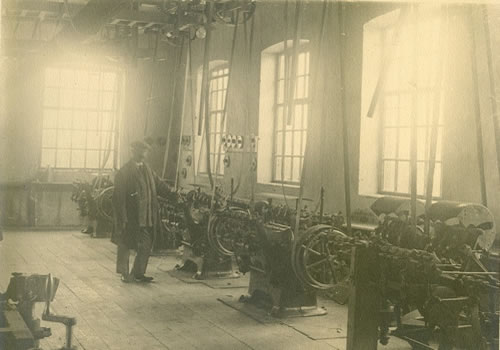

The first e-mail she sent seemed to be just a sentimental look back into the region and town where her family had originated. It was about her and her three grown sons: Jonathan, James and Judson traveling together from California to Biala Podlaska in today's Eastern Poland. In addition to Biala Podlaska, she was also interested in Miedzyrzec Podlaski, Lodz, Wroclaw and a mysterious place spelled "Switliki" which was supposed to be close to Biala. In order to place the first figurative piece of the puzzle, some background was needed, and on this occasion it was the 400-year history of the Jewish Community in Biala. The first Jews were already settled there in the 16th century, but the first written evidence of Jewish existence is marked in the local ducal privilege issued to Biala in 1621. In those days the Jewish inhabitants were mostly merchants, craftsman, innkeepers, credit givers, many also employed in the production and sale of alcohol. Throughout the 19th century this part of Poland was in the "Russian Partition Zone", so the local economy went into stagnation until the 1860's, when revolutionary legislation making every citizen equal before the law brought some economic change. The other sign of progress was the train line connecting Warsaw with Brzesc (now Brest, Belarus), which went through Biala Podlaska. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish population in Biala constituted about 65% of the total. The Jewish community managed five synagogues, six prayer houses, a Jewish hospital, three tenant houses, a Talmud-Torah, seven shops, and a few squares and gardens. In the 1923 regional council elections, Jewish parties managed to secure eleven seats in the Biala city council. In the period 1918-1939, between wars, there were four Jewish newspapers published in Yiddish: Zionist "Bialer Wochenblat" and "Podlasier Lebn" as well as "Naj Podlasjer Lebn" and "Podlasjer Sztyme". Biała, at that time located in central Poland, was a small city, looking proudly into the future as the modern aviation and timber industry developed.

Machines in the Rabbe timber yard.

Jewish Market

The part of the puzzle background is complete, now we must fit onto that background the first historical event. That well-preserved piece of the puzzle is solid and well preserved. On September 10th ,1920 Marshal Pilsudski personally decorated the local army commander with Virtuti Militari decoration, at the Renaissance style rail station in Biala Podlaska. This event is memorialized on the decorative plaque recently unveiled at the train Station in Biala.

The Rosenzweigs were one of the Jewish families in town, long rooted in this Podlasie soil that by the 19th century had already begun showing the first traces of modernity. Usher, born in 1906, became a city clerk and cashier in the city council of Biala. His picture depicts a smart man in a well cut suit. He would definitely have been part of the city intelligentsia of that time. Usher was married to Hudes Zajgman, and they had two children, Israel-Itzchak born in 1933 and Gitta born in 1938. Motel Rozenzweig, the brother of Usher, opened a successful bicycle shop in Biala. Political and economic instability during the 1920's, along with creeping anti-Semitism, caused Motel to make hard decisions. The Biala business seemed insufficient for this self trained mechanic, so in the '30s he married girl from Biala who had emigrated to the United States, which allowed him to become the US citizen and move his business to America, where he became known as Martin.

When I met Gitta in Warsaw she seemed to be in her early 60's, a tall, blond, elegant woman, who even after thirteen hours flight from Los Angeles was ready for several hours drive to Biala. We had corresponded before her arrival, and I had learned some parts of the family story, including how she had survived. At this point, I had learned how some elements of the puzzle looked like in their still undefined shape. Here are some of the things I learned:

1. The family was from Biala Podlaska.

2. She was born in Wroclaw.

3. She was saved by nuns in an orphanage in Switliki.

4. The nuns wore ordinary clothes, not habits.

5. She had lived in Lodz.

6. The family apartment was located on Grabanowska street.

7. She had lived with the Dziekanski family.

8. She had emigrated to the US.

If you put those pieces of the puzzle in chronological order, they seem to make sense, but the question remains how to fit them together. Biala Podlaska and Wroclaw are far apart. In fact, in 1938 Wroclaw was not even in Poland, it was in Germany. However, I did locate an orphanage in the Wroclaw district of Swiatniki which used to be run by nuns. Things were starting to fit together. But why would the family move 500 kilometers across central Europe from Biala Podlaska to Wroclaw?

The only way to find this out was to go with Gitta and her three sons to Biala and explore the "puzzle board" in its present shape. Today, Biala is a peripheral city close to the Poland-Belarus border. Its large market square is the only reminder of its former importance as a trading center. Its architecture is very patchy, with mostly two-story brick houses, plus many picturesque wooden structures from the 19th century. Finding things distinctly Jewish was difficult. We explored spaces where buildings used to stand. A large empty square at Szkolny Dwor street once held a synagogue. Now it seemed as if something had been literally ripped away, which is the truth. There are two obviously remodeled buildings that used to be Hassidic shtibls. The old Jewish cemetery accommodates a cinema building from the Communist era as well as a monument to local people who were deported to Siberia. The new Jewish cemetery, with few stones left, includes a small memorial plaque to local Jews who were killed in the Holocaust - it is the best preserved Jewish site in town.

Synagogue building at Szkolny Dwor street in the 1940's.

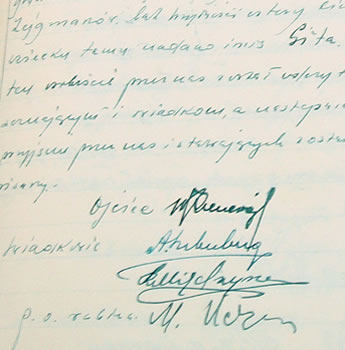

Now let us begin to put our puzzle pieces in place. We visited the local population registry office and inquired about documents of birth, marriage and death. Within a few minutes the very helpful lady produced books of the Jewish community from the 1920's and 1930's. The painful void of Jewish life outside the windows of the office began to be filled with thousands of names and surnames of families who had once lived here. In little more than one hour we had the beautifully hand written marriage record of Usher and Hudes, then came the birth record of Israel Itzchak from 1933, and finally the birth record of Gitta in September 1938, hand signed by her eloquent father, stating that she had been born in Biala, not Wroclaw. Only later did I learn that "Wroclaw" had been written on Gitta's French papers after the war so as to facilitate her emigration to the United States as a person born in Germany, therefore subject to German emigration quotas. She had in fact been born and "raised" in Biala. Though she was not raised there for very long, because a year after her birth, on September 13th, 1939, Biala was occupied by the Germans. Thereafter, it was occupied for over two weeks by the Soviets, and on October 10th retaken by the Germans on the basis of the Hitler/Stalin pact. This was typical totalitarian territory juggling, as had been going on in those areas for the last 200 years.

Little excerpt from Gitta's hand written birth certificate with a hand signature of Usher.

First signature in column.

Usher Rozenzweig (1906-1942)

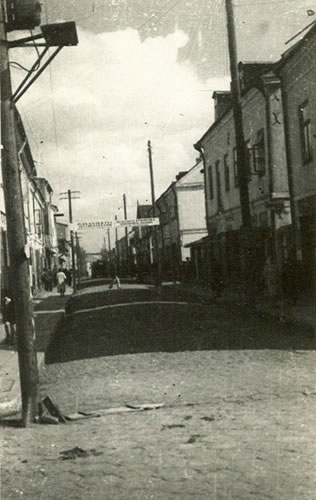

On December 1st, all Jews over the age of six were required to wear the Star of David arm band, and the Jews were confined to Grabanowska, Janowa, Prosta and Przechodnia streets. In this way the ghetto was created. The Rosenzweigs lived on Grabanowska street 8, just next to the official entrance gate to the ghetto. The living conditions in the ghetto were deteriorating day by day as new waves of Jewish deportees from other parts of occupied Poland were arriving in Biala. There was a camp for Jewish Prisoners of War. Jews from as far away as Cracow were sent there temporarily, waiting for the next developments in the "final solution" Nazi policy, which at this early stage were not yet known even to the Nazis themselves.

Grabanowska street in 1941 with entrance gate to the Ghetto.

The fate of European Jews was sealed by the Nazis in the winter of 1941/1942, and the Polish Jews were the first to feel its consequences. In the spring 1942 the infamous 101st Auxiliary German Police Battalion from Hamburg was sent to the Podlasie area. Their activity is well described in Christopher Browning's book "The Ordinary Men". The round ups in Miedzyrzec and Biala were to be the first extermination experiences of these ordinary police men, commanded by Major Wilhelm Trapp in Podlasie.

At dawn of June 10th, 1942, 3000 Jews from the ghetto in Biala were assembled at the square in front of the synagogue. There was general turmoil as some people had already heard news of what had happened to other Jewish communities from the Lublin district in the Spring of the same year. Some people attempted to run to the forests, some were shot. Here comes another fact to add to the Rozenzwieg story: Some witnesses claimed to have seen Gitta's brother Israel Itzchak being shot in the ghetto streets. Was it on that day in June in 1942? There is no death certificate for him, because the last entries in the registry books occurred in Spring, 1942. From that point we face the void again, empty pages. This part of the puzzle will remain blurred forever.

From the synagogue square the people were escorted by the police to the train station. On the next day, 3000 Biala Jews were crowded into cattle cars and deported to the death camp of Sobibor, 85 kolometers from Biala. A few days later, Emanuel Ringelblum, the genius chronologist of the Warsaw ghetto, wrote in his diary:

I had a talk the other day with a friend from Biala-Podlaska, head of the Social Relief organization. He had been assisting with the population "transfer" (it would be more correct to say "transfer to the other world") to Sobibor near Chelm, where Jews are choked to death with gases. My friend asked in anger, up to when... how much longer will we go "as sheep to slaughter?" Why do we keep quiet? This question torments all of us, but there is no answer to it because everyone knows that resistance, and particularly if even one single German is killed, its outcome may lead to a slaughter of a whole community, or even of many communities. The first who are sent to slaughter are the old, the sick, the children, those who are not able to resist. The strong ones, the workers, are left meanwhile to be, because they are needed for the time being. The evacuations are carried out in such a way that it is not always and not to everyone clear that a massacre is taking place. So strong is the instinct of life of workers, of the fortunate owner of J-cards that it overcomes the will to fight, the urge to defend the whole community, with no thought of consequences. And we are left to be led as sheep to a slaughterhouse. This is partly due to the complete spiritual break-down and disintegration, caused by unheard of terror which has been inflicted upon the Jews for 3 years and which comes to its climax in times of such evacuations. The effect of all of this taken together is that when a moment for some resistance arrives, we are completely powerless and the enemy does to us whatever he pleases. It will nonetheless remain completely incomprehensible, why were Jews from villages around Hrubieszow "evacuated", under a guard of Jewish policemen, and not one of them escaped while on their way, although each of them knew where and towards what they were going. There will not be an expert able to explain why 40 halutzim from an agricultural kibbutz consented to be led to slaughter, though they knew what had happened in Vilna, Slonim, Chelmno, and other places... Not to act, not to lift a hand against Germans, has since then become the quiet, passive heroism of a common Jew. This was perhaps the mute life instinct of the masses, which dictated to everybody, as if agreed upon, to behave thus and not otherwise. And it seems to me that no incitements, no persuasion, will be of any use here; it is impossible to fight a mass-instinct - you must submit to it." 1

The summer of 1942, with its turmoil, hesitation and lack of alternatives, must have been horror for the over 5,000 Jews remaining in Biala. Almost every week another Jewish community from the Podlasie region was deported or killed on the spot. News of those actions must have reached Biala, especially because part of German Police Battalion 101 was stationed in the city. In August there were a few roundups of Jewish men in the Market Square, to have their documents inspected. After every of such action there were victims, with some smaller groups deported. The uncertainty must have reached its zenith. This period brings a lot of guesses in our quest to fill in the blanks of the Rozenzweig puzzle. Were Usher and Hudes deported? Probably not, as they would have been too well established in town and too young. Such people were not taken at first. From another bit of hearsay we learn that Hudes was seen in the nearby Miedzyrzec Ghetto on its deportation in Autumn of that year. Both parents were probably staying at their house on Grabanowska 8 in the ghetto just across the street from the synagogue square. The trauma of losing one's first born child was paralyzing, but also forced them into action to save and shelter the one child left.

Shelter For Gitta

From this point our history puzzle becomes fragmented, by relying on Gitta's memories and a few documents, we can assume that the parents either secured a shelter at the house of a Polish teacher in one of the rural schools in the region of Biala. Or as it is stated in a letter send to Gitta by Ida, who took care of the girl after the war "your parents , wanting to save your life, decided to take the risk of dropping you off by the road side and letting you run into the fields where they knew there were a few nearby farms and where you could seek shelter and not be identified as a jew because you did not at all look Jewish... ". The teacher's family who took the girl in was named Czekanski. The last well preserved puzzle pieces of this period are the painful pictures of the Biala Jews being collected in the market square for the deportation and marched away. Those pictures represent the last faded images from 400 years of Jewish life in Biala Podlaska.

Nazi Roundup in Biala Podlaska 1942 - Grabanowska Street

(the tall building on the left side in the background is Grabanowska 8)

Nazi Roundup in Biala Podlaska 1942 - Market Square.

In 1942, Sukkot fell between September 23rd and October 2nd. The final deportation of the Biala Podlaska Jews started on September 26th and finished on October 1st. Organizing the roundups on Jewish high holidays was a common practice of the Nazis. The night before September 26th, the entire ghetto was surrounded by police and military units. In the morning they started to crowd thousands of Jews into the Main Market Square. Anybody resisting was shot on the spot. Brutality prevailed. There was bloodshed in the Jewish hospital. Some people with work permits were selected and sent to nearby labor camps. Thousands of others were put on horse drawn wagons or forced to walk to the Miedzyrzec rail station. Miedzyrzec became an assembly point for local Jews of Podlasie before their deportation to Treblinka. It was a vestibule to hell. The German Police found it difficult to pronounce Polish Miedzyrzec, and even more difficult to use Yiddish Mezritsh, so they coined the nickname Menschenschreck, meaning "men's horror". Most Biala Jews were gradually deported to the Death Camp in Treblinka until Spring, 1943. Usher and Hudes were probably among this last group to leave Biala for Miedzyrzec and then to Treblinka. Before this happened, Gitta was taken to safety at the Czekanski farm. Gitta Rozenzweig ceased to exist and was reborn as Marysia Czekanska.

The pieces of our history puzzle for this period again become only vaguely visible in the general turmoil of occupation brutality. The Czekanski's, concerned that they might be betrayed, decided to find some other safe shelter for their new Jewish daughter. The large posters hung by the Nazis on every city corner made it clear that for providing any help or hiding a Jewish person in occupied Poland the entire family would be executed. The Czekanskis must have been aware that sheltering one girl, with restricted food rations for everybody, required that a few people would know about it, and it took only one to betray them. Therefore, the Czekanskis found a little orphanage run by the Catholic nuns in the nearby village of Sitnik, just 15 kilometers north of Biala. This place was to become an ark, inside of which Marysia Czekańska would endure the lethal Nazi storm in Poland.

Just before Gitta's arrival in Poland in 2010 I located the Congregation of the Daughters of the Holy Heart of Maria, who used to be active in the Biala area just before the war. After a little search I learned of an orphanage that the sisters ran throughout the war in the small village of Sitnik. The nuns wore ordinary clothes, rather than habits. This was a gratifying moment, when the pieces of the puzzle started to fit together, a moment when an imagined "Switliki" became an actual dot on the map called Sitnik.

The best personal description of the orphanage was provided by Sister Aniela Szoździńska, head of the institution. In 1951 she wrote "Short Story of the Orphanage in Sitnik."

"In 1939 The Charity Society in Sitnik suggested the Congregation of the Daughters of the Holy Heart of Maria to take over the orphanage in Sitnik. This was accepted on August 1, 1939. Our work has started in very hard conditions and complicated circumstances. There were always around 50 orphans from 2 to 14 years old. The orphanage was located in a very picturesque rural area. The institution was co-educational - boys and girls were mostly from the area of Sitnik and its larger administrative district. The upkeep costs of the children, as well as some construction fund were raised due to the hard labor of the sisters as well as their personal savings. The sisters worked selflessly, not taking any payment. The constant in-flow of children caused the existing building to be too small, so a new addition was constructed from the internal funds. From 1946 the orphanage was named The Social Home of a Child and started to get the government subventions granted to all such institutions in the country.

Taking into consideration the well being and skills of children the directorship of the Orphanage laid a great stress on versatile education of children, with an aim of upbringing useful members of the holy church and socialy aware citizens of the beloved country of Poland. Our pupils after finishing the primary education were advancing to different schools in the region, which was often connected with changing the place of their residence. After being sent to other orphanages they would never loose contact with their home place in Sitnik. The contact with former pupils was constantly up kept though letters and meetings during summer and winter holidays.

From 1939 till the moment of the house liquidation, or rather moment when we were fired because the house got nationalized on the 1 of August 1951, there were over 700 children-orphans who were given education and upbringing."

The Head of the Orphanage

Aniela Szoździńska

Gitta brought a few pictures with her from the war period in Poland. There was one photo on which we could see a woman sitting on concrete stairs in front of a large wooden building, with Marysia Czekanska on her lap. This was not her mother - this was one of the nuns taking care of her. When we visited Sitnik, the wooden building of the orphanage was no longer there. On that plot of land there was now a square school, built in the Communist era. The only structures remaining were the stables that had been part of the orphanage estate. The older village inhabitants started to share stories of the orphanage with us. In a few minutes we were standing on the remaining history relic, the concrete stairs that once led to the wooden orphanage building. These were the stairs in the photograph. The only other thing remaining was a little shrine devoted to the Holy Mary, standing in solitude on the edge of the village road.

Gitta with one of the nuns on the concrete stairs leading to the orphanage.

The next day we drove to Lodz, where Gitta lived for a few months in 1945. On the way we decided to pay a visit to the Congregation of the Daughters of the Holy Heart of Maria in Nowe Miasto nad Pilica. While speaking to the sisters by phone, I found out that they had virtually no information about Sitnik, only a few pictures and the above cited short description. But, in completing the puzzle, sometimes "VIRTUALLY no information" is enough and can in fact help to complete the entire picture. We came to the Nowe Miasto late in the day, and were welcomed in a small room just next to the entrance, but still outside the convent. The room felt like a no-man's land between the profane world outside and the sacred world inside the convent. The two Sisters, Maria and Teresa, were very hospitable, but kept a natural distance listening to our story. I was uncertain about how much to disclose - should I tell the story of Gitta Rozenzweig, or maybe only Marysia Czekańska? How would they react? Did they know that their fellow Sisters hid Jews during the war? I focused on Marysia Czekanska's story, observing the increasing interest in the Sisters' faces. Once the Sisters realized that Gitta was one of the orphanage children, there was an outburst of emotions - emotions one can experience only in a very good family life, genuine happiness at the moment of meeting a relative who had been so dear but lost for over fifty years. Gitta, Jonathan, Judson and James were hugged and kissed as if all four were little orphans returning home. In that moment the Sisters began leading us through the doors and courtyards of the convent into the internal circles of the nuns' life. From a dimmed corridor we were led into a fully illuminated room with a long table in the middle. The table was covered with all kinds of food and sweets waiting just for us - a short trip from purgatory to heaven. In the short conversation we learned that there was not much left of the Sitnik documents, because the property had been nationalized by the Communists in 1952. There were also no Sisters old enough to remember. We were just given a tableau with 10 pictures of Sitnik: wooden building, Sisters, children, concrete stairs, priest with children, and a small shrine of the Holy Mary. All these pictures fit with those few pictures that Gitta had brought with her. There was no doubt that this was the right place, but who could shed some more light on Gitta's story? After much conversation and many horrible stories about the war period, I gradually introduced the topic of Jews in the convent, indicating that Gitta was one of those cases. Both sisters showed even more compassion and understanding. Sister Teresa, Head Mother of the entire convent in Poland, started to remember writing something on the Jews in the convent during the war years. She disappeared to the archives and in a few minutes brought an article on the various orphanages run by this convent during the war, which included a short summary of Jewish children hidden under false identity all over Poland. Under various addresses in Warsaw eleven children had been saved, in Nowe Miasto two children saved, in Skorzec two children saved, in Otwock sixteen children saved, in Swider four children saved, finally an undefined number of children saved in Sitnik, Kolno, Janow Podlaski, Wilno and Pinsk. Most of those children were never identified after the war, as they were the sole survivors and continued their life under their new war identities. The article gave some details about Sitnik. There were Christian names and surnames given to two boys, plus mention of a few other Jewish kids, and a short note on Marysia Czekanska. The note said that she was hard to hide from the Germans, and that after the war she was taken by some Jewish organization to join a family abroad. Bingo! The history jigsaw was almost complete.

At this moment, Gitta submerged into memories of trauma and desperation when, just after the war, she had been taken away from the orphanage and the Sisters. From the orphanage time period she remembered being hidden in the bunker with Sisters and other children during the bombardments, and also remembered the moment when some men were aiming rifles at one of the Sisters and the children were screaming and begging for her life. Instinctively, I then asked for the source of this article. There must be some source if someone quotes the names and surnames in detail. Mother Teresa disappeared again and in a few minutes rushed back with a thick volume - her Master of Arts dissertation! We started flicking through the pages: chapter on the war, chapter on helping the Jews, from Sitnik down to references - and there it was, "Personal Diary of Sister Jadwiga Gozdek from Sitnik orphanage". Mother Teresa made her third disappearance to the archives to come back with the diary. The hand-written diary appeared to provide the final element linking all the puzzle pieces of Gitta's life in the orphanage in Sitnik.

Chosen excerpts from the memories of Sister Jadwiga Gozdek:

"On the 25th of June 1943 I took my first convent vows and I was immediately directed to orphanage in Sitnik - village close to Biala Podlaska.....

.....I have finally reached Siedlce but on the way I was deprived of my luggage. On the way to Biala Podlaska every few kilometers there were derailed and burned trains and twisted rail lines. This was the result of activity of the local partisans who were exploding the German trains. We were all constantly unsure if we will get there as those were last months of occupation and the fights were getting more and more severe. ....

.....In Sitnik the sisters welcomed me warmly, but they were also full of anxiety as the night before there had been an Ukrainian raid on the orphanage. They were looking for young nuns to have fun with. The Head Mother was threatened to be shot. She was saved by children who refused to step away and were begging for her life. .......

.....The Orphanage was placed in two old houses without electricity or hygienic facilities. The sisters and girls lived in the larger house with veranda. The larger room was changed into canteen and day room for children. The place was very packed; a few sisters had to share one room. ......

......Our Head Mother was sister Aniela Szoździńska, there were 7 sisters in total and around 40 children aged from 3 to 19, boys and girls. ...

.....There were 15 hectares (37 acres) of land , garden , orchard and bee hives. We had a few cows, horses, pigs, sheep and chickens. Work was extremely hard, as there were no tools and all the work we did manually with the help of older children....

.....Children were mostly orphans and half-orphans due to war. They were coming to us terribly dirty and insect ridden. Often we had to burn all of the child belongings on the arrival. They were often brought to us naked and barefoot. Thanks God we had enough food. Sometimes I was watching with pain how our children are throwing away bread. Then I was telling them about people starving all over the country. The worst situation we had with clothing and shoes. We were stitching new patches into the old ones.....

It was the worst with shoes. Father Edward Kowalik, incredible good man, devoted priest and a former teacher, the man with golden hands and heart all his spare time he was spending with children. He was able to resolve any problem. He acquired some military tarpaulin, organized a shoe maker and was personally producing wooden soles.... In this way we made shoes for all children....

......Winters 1944/45/46 were the hardest. Then we started to get some donations, but often we had to match two shoes which were different to give shoes to every child. Among our Polish children there were also Jewish children. Some of them had very characteristic Jewish features. We had a lot of anxiety and troubles connected with that especially that right after my arrival part of our house was confiscated for the German police commando station. We had to constantly hid the children and do our best not to be betrayed, because we were all aware that in such case we would be all killed on the spot. One particular girl was very beautiful and she was standing out from all our children. She had very pale and delicate complexion, blond, curly hair , blue eyes and for a long time she had it hard to learn to speak clear Polish. The Germans were constantly asking who this child was and why was she so different from the others. We were all the time saying that this is the child of a Polish nobility and for this reason she is so different and delicate. After the war, some Jewish organization has traced her and in spite of her resistance and great despair, because she got very bound with Sisters, she was taken away with force and taken abroad where she probably had some rich family. All of those children had Polish papers. The girl was named Marysia Czekańska, boys Henryk Gołubiak , deaf-and dumb Andrzej Sitnicki and others whose names I don't' remember.

In summer 1944 after the Germans retreated we were located in the middle of the front line. We spent a few hard days with children in the bomb shelters dug in the garden, because there were once Germans once Soviets starting the offensive. Next to our house there was an explosion of inflaming bomb but the trees have sheltered the house from fire and sparks. .......The nearby village was completely bombed and devastated. .... God has saved us and children, and after the war as a thanksgiving we have placed a figurine of the Holy Lady in front of the house. ..........The Germans have taken our horses....

...When for the first time we noticed the Polish soldiers with white Polish eagle on their military caps we burst into tears out of happiness. .....

.....After Berlin was taken we had some Kosciuszko Army (communist Polish army: TC) stationing at our place and they were very helpful with harvesting. They gave us horses. They were helping us with children and dreaming of their own families. Very soon they left to fight against the partisans in the forests. We were crying once we have heard the machine guns in the forests against the partisans. The indescribable pain as we knew and loved men on both sides of this fratricidal battle...."

Those few pages of bleached paper contained all the elements that we had so desperately sought, pages read aloud and translated around the generously set table in the year 2010 with Mother Teresa as our guardian angel and Marysia Czekańska as family story savior. Most of the children sheltered by the Sisters during the war were never identified in the post war turmoil. Marysia's story was different: A few months after liberation in the summer 1945 she was taken with other children for a trip to Biala Podlaska, and while crossing the market square she was identified by one of the Christian merchants. Here another miraculous piece of luck allowed Gitta Rozenzwieg to be re-born: The merchant contacted Ida Koper, a Jewish Biala survivor who had escaped the city during the 1942 round-ups and survived in Warsaw under false papers. Ida happened to be in Biala that summer in 1945, and had known the family before the war. She took it upon herself to take care of Gitta and find her family.

The moment of departure from the orphanage.

The Head Mother Aniela Szoździńska with Gitta in her arms.

The crucial element of our puzzle for that time is the picture of what was probably all of the Jewish survivors of Biala taken in 1944 or 1945, with a large banner over their heads announcing continuation of the Sukkot festival from 1942. This festival had been marked with killing, but now was to represent endurance and continuation by those few survivors in the picture. Gitta is in this faded picture, but neither of her parents is.

After war Sukkot Festival celebrated by Biala Podlaska survivors continuing the brutally interrupted Sukkot in 1942.

Ida first contacted the Biala survivors society in Lodz who got in touch with Gitta's uncle on her mother's side, David Zajgman, who lived in Paris. Then she and the society contacted the brother of Usher in the US, Martin Rozenzweig. Ida went to the trouble of taking the girl out of the orphanage, paying the bribes and other fees requested on various administrative levels. She also helped alleviate the emotional stress that seven-year-old Marysia/Gitta had experienced, having been torn from her sisters and orphanage. Finally, through Lodz and Wroclaw Gitta got to Paris, from whence Gitta emigrated to join her uncle Martin in the United States.

The story thus revealed, with all the available puzzle pieces put together, creates a telling portrait of what the life of Gitta/Marysia was like during the war. All of the elements support each other, held together by an undefined power that might be called "luck" or "destiny" or "the Lord's Plan." Without all of those pieces, the story of Gitta's life would never have been completed, neither in 1945 nor in 2010.

P.S. For Jonathan, James and Judson, the possibility of tracing back the family story was definitely an eye opener, a life changing experience. They are constantly adding new puzzle pieces and information to the Rozenzweigs' family story. Jonathan, who literally fell in love with Poland, and who is a frequent guest to Cracow, has recently shown me a picture of Usher, (which I recognized from our search), as well as Usher's signature, copied from Gitta's birth record. Both of which have been artistically tattooed in full color on his right forearm. My surprise as to where the research can carry a person is endless, but in the same moment, I experience the satisfaction that in this pop-cultural way he shows the importance of the entire history experience. And he begins to create a new puzzle to decipher in the future...

Tattoo of Usher and his signature on Jonathan's right forearm.

Written by Tomasz Cebulski

Edited by Murray Gould

-----

1 Kermish, Joseph (Ed.), "Emmanuel Ringelblum's Notes, Hitherto Unpublished", Yad Vashem Studies VII, Jerusalem 1968, p.178-180.

May 2008 - Wislica

In early May 2008 I got an e-mail from Jane with request to organize just a one day trip to the city of Wislica for 3 people. The project sounded ordinary and uncomplicated and was not looking like being connected to any particular research. Just a one day excursion to see the city and what was left of the Jewish Heritage. I was not given any details, but suspected some family history behind. When Jane started asking questions concerning security in Wislica I sensed layers of mistrust and this special and so common "love and hatred" relationship to Poland. That was the moment when I found out the she was coming with her father Jacob who had lived in Wislica before the war.

A little detail that changes everything......

I started to prepare some database about Wislica in general and Wislica Jewry in particular. I studied the Yitzkor book of Wislica, started to look for genealogical documents from this city and read most texts available from Wislica rich history. The lecture was both surprising and illuminating. I discovered that this small village, around 90 km away from Cracow, can boast of its IX century origins. This was the supposed capital of the Wislanie tribe which only later merging with other Slavonic Tribes became the Kingdom of Poland. In its Medieval history Wislica was one of the major fortified castles of Kazimierz the Great and in 1347 the King had proclaimed the Legal Charter of Wislica which regulated all legal and social issues in the Kingdom of Poland. The later history made Wislica a more and more provincial town and in XIX century the lack of rail line connection degraded it from a town to a village.

Jews were first mentioned in the city documents in early XVI century. They were known as city traders, competing with Christians, which often led to frictions resolved few times by the royal authorities. Gradually, on the basis of various privileges, the local Jews specialized in the production and sale of vodka, beer and mead. XIX and XX century had brought the rapid growth of Jewish community which in 1939 reached over 60% of the general village population. During the Holocaust the German Nazis established a ghetto in Wislica which in 1942 was liquidated and residents deported to Treblinka Extermination camp. One may say - a repetitive history of one from few thousands of pre war Polish shtetls - but for me it was becoming special due to the person I was to travel with.

We met in the early morning in Cracow. Jane was smart and friendly and she introduced me to her sister Esther and their father Jakob. Jakob was already in his 80's but he still had this sparkle of a teenager in his eyes, maybe because he was back to the country of his childhood for the first time since 1945. The road went smooth and fast as we were discussing the complicated Polish-Jewish history and with every kilometer closer to Wislica, I was finding out more and more from Jakob's story. The family had a textile shop, he was a boy helping with business. There were Christian and Jewish customers, he was traveling to Cracow to buy textile with parents. Life was hard but the sense of community and young age was making Wislica home.

We arrived to the Market Square of Wislica and realized that it is more a village than a town and there is not much left from a splendid royal history of this place. We found the place where the textile shop used to be, still a shop, but with grocery now. Then, I was prepared to locate the plot of land where the synagogue used to be, which now has a communist era apartment building standing. The place of worship of God changed into an ugly tribute to social realism. Our presence was raising general interest and soon we started to talk to people, asking questions about the past. Some stories followed but nothing about Jakob's family. The people showed us where the mikvah was - almost nothing left, they indicated a way to the cemetery and shared some war stories they remembered. Cemetery was a shock even for me, although I had seen hundreds of such places before. Every time they raise the same emotions of a need to explain at first then helplessness and finally shame. It was devastated partly during the war as stone was used by the Nazis for road construction but partly after the war by people using the stone for various purposes. Now, it is piece of overgrown land with few remnants of matzevots sticking out and covered with graffiti. Jakob took it calmly and at least for me seemed to be understanding.

Around noon we headed towards the dominating over the village gothic basilica from XIV century, the only reminder of the past glory of Wislica. A lady acting as a caretaker was very friendly and she took us around the building with great engagement, including the under basilica Romanesque church excavations. The basilica and a nearby museum had nothing about the Jews. Sometimes you can have a sense of looking for some long-lost civilization but only then do you realize that they lived here only 70 years ago. More, in this case the person standing next to you remembers those people and their faces. Jackob is one of them. It was only 70 years ago, time of a very systematic, programmed destruction of not only the people but also their culture and remaining memory about their existence. Destruction initiated by Nazi Germany and carried on by Communist Regime on those lands. The sad conclusion in that moment was that the excavated baptistery from IX century was better preserved than the Jewish cemetery still used for burials in 1940.

Having this in mind Jakob seemed to be a person from some other planet, if not galaxy, and by all means it was important to find out how he came or was preserved to this reality we know today. I have perceived his appearance on the market in Wislica in 2008 as an act of commemoration to the Jewish Community which was gathered on this square in 1942 to be deported to Treblinka. His presence in some way was a posthumous statement of Wislica Jewry about the failure of the meticulous German genocide policy. That was my image but Jacob seemed to be free of any ideology or grandiose needs of proving anything. He was just there to experience the place, pay tribute, calmly register the changes and find one Polish Christian family. How come that against all odds, 63 years later, Jackob was back to Wislica???

On the way we tried not to talk too much about Jakob's war experiences but I learned later that he had fled the village before the deportation in 1942. In spring of that year there were rumors circulating about Jews being gathered and deported from nearby villages. Once the Jews started to disappear from the region, Jacob and two of his friends decided not to show on the round up order in Wislica square but to leave the village. They found a shelter in some caves nearby but with winter 1942-43 coming they needed to change the hiding place. It wasn't so much due to the temperature but rather the foot prints they were leaving on fresh snow which might have led to them being discovered. Jakob reminded himself the Polish farmers family of Kowalski who were the former customers in their textile shop. Having no other options, he decided to give it a chance. At night the three Jewish boys crawled to the Kowalski farm and knocked at the window. Waleria, the mother of the family, was scared to death but led the boys to the kitchen and called the family of five children and husband Stanislaw. The Kowalski's knew that sheltering the Jewish boys they risked the lives of the whole family of 7 people. This was made clear by the German occupier. They also knew that hiding 3 boys is a challenge with extra food rations already very limited due to the German regular confiscation of food from farmers. In those conditions saving boys would take the engagement of the whole family when the possible betrayal could come anytime and from anybody.

The family debate lasted and it was finally Waleria who finished it with a statement that protecting them is just the right thing to do. The family prepared the hiding place under the barn floor and three Jewish boys were located there. At this moment the future was unknown and nobody even predicted that they would leave this place for good only 26 months later.

So here we were, at 1 p.m. on a sunny May day in 2008, in Wislica with a local war story told by Jacob. The only missing element was the family of Kowalski. We asked people in Wislica, nobody knew this surname. Local registry office brought no revelation. Catholic priest in Wislica didn't know them either. Jackob said that it had been some place outside the city, probably on the way to Chroberz and that the farm had been large. So, lets drive to Chroberz and on the way stop in each and every larger farm area. After visiting few communist run and then abandoned farms and creating hundreds of possible versions of what might have happened with Kowalski family, there were more questions then answers. Caves seemed to be a good hint and finding them might have brought us closer to Kowalski farm. Just a little orientation in the map of the region and... caves were everywhere. We were in the valley of Nida river with gypsum rocks all around. Geologically, it looks like a Swiss cheese. The cave part of the story can't help too much.

We decided to visit all the Catholic Parishes around but both priests in Zlota and in Chroberz, although willing to help, knew nothing. Frustration grew especially that it was already 3 p.m. and we still needed to drive back to Cracow. We came to Chroberz to give it a try at the local museum. Exhibitions, maps, documents brought nothing new. Finally, the director was kind enough to call personally three oldest city inhabitants to ask for Kowalski. We where sitting there in director office ready to put down the Kowalski address. People must remember.

To our surprise, no one has seen or heard of them. It was just as if we had come to the wrong place on Earth or as if that world had never existed and resuscitating it would bring no result. A little victory of the Nazi or Communist system which seemed to kill something for good. Kowalski's haven't existed. I became even suspicious that maybe Jacob misremembered the surname and I started to check its all possible variations. Not that it would bring something.

The last chance were the people working in the population registry offices in Chroberz and Zlota. I decided to start with Zlota but when we got there, the office was already closed. They close at 4 p.m. and it was 10 minutes past. When I was going out, obsessively thinking what else can be done, there came a farmer saying that if we rush up the village we should find the registry clerk walking back home. With no time to loose, we drove up the village and picked up the registry lady on the way. She was nice enough to reopen the office and listen to our story. With her help, we scanned the census books from 20's and 30''s to find...... nothing. When we were about to leave, she said that there was no Kowalski here but it ringed the bell for her on the other side of the Nida river in village of Zagosc. She made a few phone calls and indeed there were Kowalski in Zagosc somewhere. "Somewhere" sounded very vague especially at 4:30 p.m. of that day.

Zagosc was the other side of the valley so we drove fast, knowing the only police speed control was in Chroberz. We were there 3 times already on this day. We started with a church in Zagosc and approached people who were decorating round church chapels. The man in a black shirt, who welcomed us, would make a good Kowalski. At this time of the day we wanted to see Kowalski everywhere. He happened to be the parish priest and he just showed us the lady decorating the chapel. "She is Kowalski for example" he said. The feelings of relief and panic came together. How to brief this lady a story of her grand parents saving 3 Jewish boys? Does she know about it? Does she want to know? Does she want the others around to listen? How would she react? She was puzzled but very opened and immediately called the husband to come because she was just married to Kowalski.

Only 15 minutes later were we sitting at the table in Kowalski house, telling the story. Jacob, Jane, Ester and me facing 3 surprised generations of Kowalski who were doing their best to receive us with the best food and treatment possible. The puzzles started to fit together, the family possessed a farm close by during the war and their grandparents were Stanislaw and Waleria. Unfortunately, they had died in late 40's and of their 5 children only the youngest, Tosia, was still alive - she lives in Wieliczka, close to Cracow. This afternoon it was the first time that those people heard the story of Jacob. They were never told this story by their parents as in the Communist period it might have brought some problems for the family. The only one that remembered was the youngest of Waleria's kids Tosia and Jacob too had a memory of her bringing food to the barn shelter and playing with 3 Jewish boy different games. But Tosia wasn't there she was in Wieliczka.

That afternoon we still visited the cemetery to pay honors to Waleria, Stanislaw and 4 other children. The last two things troubling us were the cave and the farm but here one of the Kowalski came with help. He took us to the area where the farm used to be. Unfortunately, no buildings were left but Jacob recognized the site. Around 5 minutes drive were the Skorocice caves which served the Jewish boys as first and last shelter. Just before liberation in winter 1945 they were afraid that the front line may destroy the farm so they moved back to the caves after 26 months spent under the barn floor. That was the last time Jacob saw the Kowalski family until this May in 2008.

The day was over and complete and even today I wonder how, if needed, we can stretch the time for our needs. The wish of Jacob was fulfilled thanks to his memory (he never gave up believing that he remembered the family name correctly), endurance (we had no time to eat on this physically straining day) and wish to face Poland and Wislica against all bad memories and stereotypes accumulated in the last 63 years. Jacob against all odds came with his mind opened which provided final success.

P.S. The next day we visited Tosia in Wieliczka. She was the youngest daughter of Waleria and Stanislaw. Jacob and Tosia recognized each other and started to share stories connected with the hiding place in Kowalski farm. Two older people, still young at heart, sharing the same stories, 63 years and two totalitarian systems later.

Written by Tomasz Cebulski

If you are interested in publishing your personal research story please contact us.

You can find more travel itineraries at TOURS, SITES, PAST PROJECTS or HOLOCAUST EDUCATION.